With Storm Arwen’s N’ly gales providing a climax to the month of November and then the first week of December being hideously unsettled, it would be easy to forget that the majority of November was characterised by very light winds and comfortable mildness.

To summarise the month…

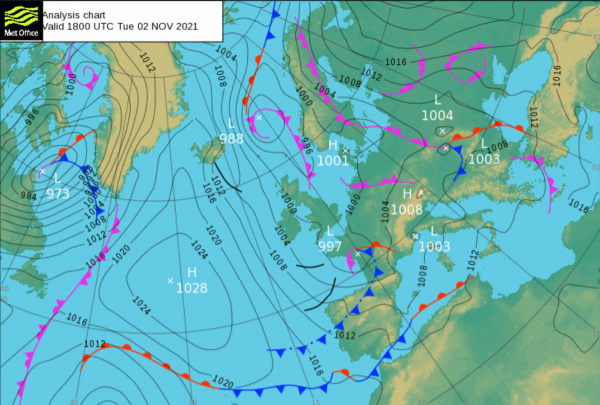

Week 1: The airflow was slack because a very shallow low-pressure system was resident over France.

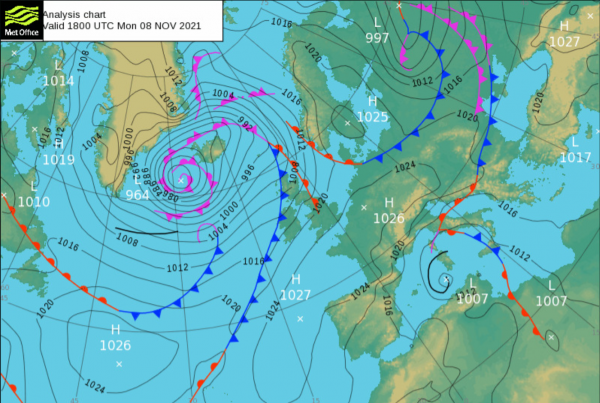

Week2: The low was replaced by a belt of high-pressure that stretched from the Azores to central Europe.

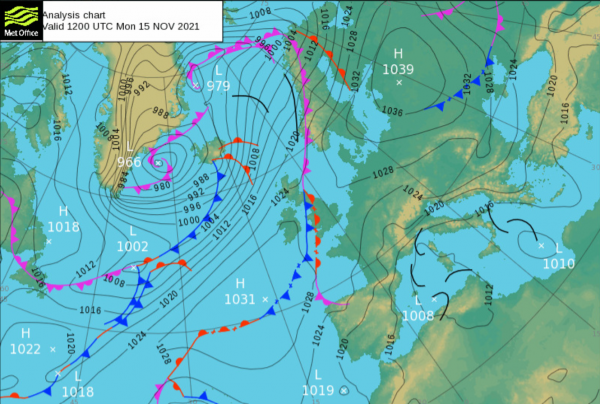

Week 3: The Channel Islands lay in some kind of no-man’s land area (known as a col) between a number of equidistant weather-systems, none of which seemed to exert any dominant influence.

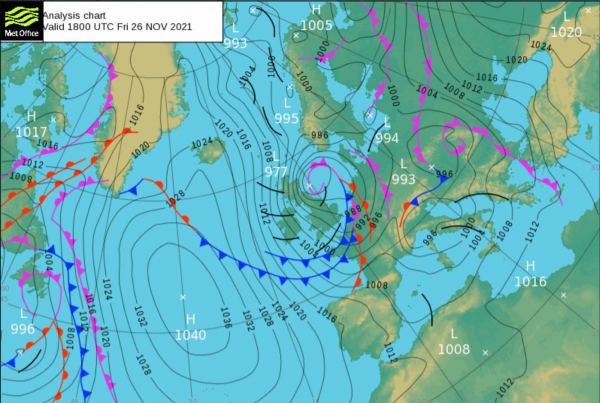

Week 4: With deep low-pressure systems spinning from Iceland, through Britain and into Europe, the wind really started to howl, and it brought some pretty frigid Arctic air with it.

Throughout the first three weeks of the month, the one common factor was the wind (or lack of). It was just so light and blissfully comfortable! Briefly blowing light force 3 to moderate force 4 every now and then, but spending the vast majority of the time breathing very gently at just light force 1 to 2. The air at the surface wafted in from a number of different directions, occasionally from the cool dry continent, occasionally from the mild moist ocean. Sometimes (generally when the pressure was high) the vertical movement of air was downwards, causing the clouds to squish thin and splurge wide. Sometimes (generally when the pressure was low) the air would rise rapidly, causing the clouds to grow tall, billowy and dramatic, producing some heavy showers and the threat of thunderstorms.

It was during the first week of November, when the pressure was low, that some really really interesting phenomena occurred… Caught on cameras around Jersey and shared widely on social media, a number of waterspouts were spotted to the south and to the east. For those who aren’t already familiar with this meteorological terminology, a waterspout is the marine equivalent of a tornado… a rapidly spinning column of air, made visible by a mixture of condensed water vapour (just like in clouds) and all the splashes and spray that are entrained into it.

Water Spouts are similar in appearance to the spiralling vortices that come into existence when you pull out the plug to drain the bath. They stretch between the base of a cloud and the sea surface (it should be noted that they are also quite common on large lakes). In their early stages they can be spotted either in the sky as a flailing tentacle reaching down from the cloud (this is known as a funnel cloud) or on the surface as a distinct disc of ruffled water and sea-spray. In either case, this would definitely be something for aviators and mariners to keep a sharp eye on, but it is really when the funnel cloud can be seen to connect with the sea-spray that the feature has reached maturity and can be called a waterspout. At this point, it almost takes on a life of its own… staggering erratically and unpredictably. Depending on many different variables, but most especially the heat (available energy) at the base and how this contrasts with the coldness at the top, the waterspout may only live for a few minutes or it could live for as long as an hour, possibly causing damage to boats or maybe even making landfall and wreaking havoc to beaches and coast-roads. Very impressive to look at, but with wind-speeds of between 50 and 150mph, they are definitely not something that you want to get very close to.

Waterspouts tend to form more readily than tornados (their land-based equivalents). Unsurprisingly, they also tend to be less destructive. They are most common in the tropics, but also quite common in many parts of Europe, including the English Channel. The most favoured conditions are when the sea is much warmer than the air in the higher atmosphere (so late summer and Autumn are prime for us) and when the wind is very light but with some type of rotation initiated at the surface (most likely by the flow of air around a headland or peninsula). There is rarely a year that passes without some report of one being seen around the Channel Islands, or at least a number of funnel clouds. Sometimes these are caught on camera, sometimes not. Of course, especially as we get into October and November, there could be many that occur during the night time… and how would we know about those? Well the answer is that they might leave some sort of a footprint or a trail, and we think that is what probably happened with at least one unseen waterspout near a house called ‘Loup des Mers’, just near Corbiere Lighthouse.

Yes indeed, the day after November 2nd (when the waterspouts were seen around Jersey), residents Hilly and John Bouteloup noticed a couple of fish on their balcony. They thought nothing of it, putting it down to a butter-beaked seagull. However, the next morning, their daughter Avena asked them why somebody had dumped over 50 small fish all over their patio. John Bouteloup’s attention had really been sparked now, so he went outside, took a short video of the strange sight and shared it with friends on Facebook. One such friend was John Searson (Principal Meteorologist at Jersey Met) and the two Johns soon got into a conversation about the possibility of this being something to do with the weather, rather than a personal prank.

When shown John Bouteloup’s video, Paul Chambers of Jersey’s Marine Resources quickly identified the fish as Sprats (which is rather convenient if you want to make a joke or a poem about it), but the important detail is that they were small (finger-size), so it’s little wonder that, if a waterspout can visibly lift water from the sea surface, then it could also have taken these fish with it.

Paul Chambers, like John Searson, is a man with a great deal of experience and interest in marine weather and he was also quick to suspect that a waterspout was the culprit.

The next question might be how high the fish could climb the waterspout? Could they go all the way up into the cloud, like Jack and the Beanstalk? Well you might not believe in ‘fairy tales’ but this ‘fishy tale’ certainly doesn’t seem inconceivable, given that we know hail stones of similar size and weight regularly rise and fall within convective clouds, eventually falling to the ground when their weight is too great a match for the updrafts.

In the case of the Bouteloups’ garden, there was no wind damage to be seen and, funnily enough, no fish were found in the neighbouring property, so it really would have been very easy to dismiss the event as nothing but a prank. However, these extra details all tie together nicely when you observe and consider the photos of November 2nd‘s waterspouts. The waterspouts can be seen to lean at quite an angle, something close to 45°. This means that if a shoal of fish were sucked up to a great height then we would actually expect them to fall many hundreds of metres away from their source. Therefore it’s entirely reasonable to receive a localised splattering of sprats, without feeling any of the extreme winds that would have been at the waterspout’s base.

Indeed, throughout history and geography, there have been many such phenomena reported and I could easily put together a huge list of references to support this claim, but I shall let you explore for yourselves. Wikipedia is often a good starting point. Just try searching ‘Rain of animals’.

Happy reading everybody!

Big thankyou to our contributing photographers and especially to the Bouteloup family, for bringing this little story to Jersey Met, because there’s nothing we love more than a bit of weird weather.

Words by Rob Plummer (Jersey Met – Senior Forecaster).

blog.gov.je

blog.gov.je