Last month, the Government of Jersey published its Common Population Policy and, in the same week, the Minister for Economic Development, Tourism, Sport, and Culture, Deputy Kirsten Morel, introduced the Future Economy Programme in a speech to Chamber of Commerce.

The Common Population Policy and the Future Economy Programme both look to 2040 and the challenges Jersey faces.

Population – or more precisely the size of the population of working age – and the economy are intrinsically linked. Population growth can fuel economic growth; it also places demands on an economy, particularly infrastructure which can become a constraint on economic growth. This month’s economic note considers the link between population and economic growth in a Jersey context.

Anyone looking at Jersey’s economic statistics could be forgiven for thinking that all is well with the economy….

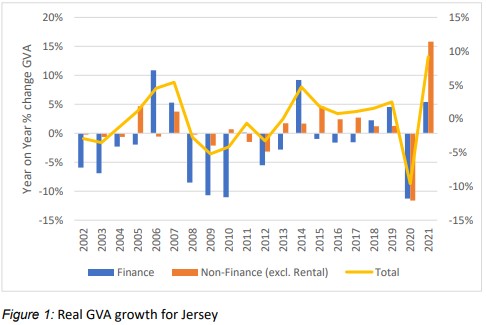

At first sight, the economic statistics suggest that Jersey’s economy has performed well and that it continues to do so. Unemployment is down, the number of jobs has increased, and as Figure 1 shows Jersey’s economy has grown in most years. Indeed, compared to other economies, eg the UK, Jersey’s annual GVA growth has been relatively good (although we won’t comment here on the strength of the UK economy).

…but digging beneath the numbers reveals a more nuanced story.

Economic value, GVA, is produced by business, entrepreneurs and the public sector combining land, workers, technology, plant and machinery (what economists term inputs or factors of production) to produce outputs such as goods and services. Economic growth can result from increases in one or more factor of production and understanding what has enabled the growth in the value of output tells us a lot about the “economic health” of the economy. Being a small island economy, two of these factors (land and labour) face a natural constraint.

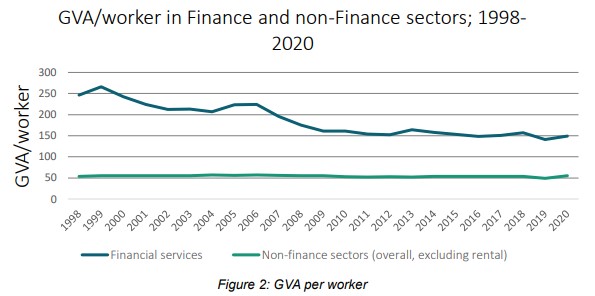

Jersey’s economic growth has been accompanied by falling productivity. What this means is that the average value of output produced by a worker this year, after adjusting for inflation, is lower than it was last year, and is lower than it was 5 years ago and 10 years ago. (see figure 2).

This means that the growth in Jersey’s economy has been driven by an increase in labour. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it is not sustainable: Jersey cannot realistically increase its population of working age indefinitely.

One consequence of productivity falling is that we are all £14,000 a year worse off than we might have been…

Falling productivity does not mean that any of us are not working hard. However, it does mean that for every hour worked, less output is produced compared to last year, and the year before, and the year before that…and this matters. It matters because it makes us all poorer. We estimate that if productivity had continued at 2007 levels we would all be, on average, £14,000 a year better off.

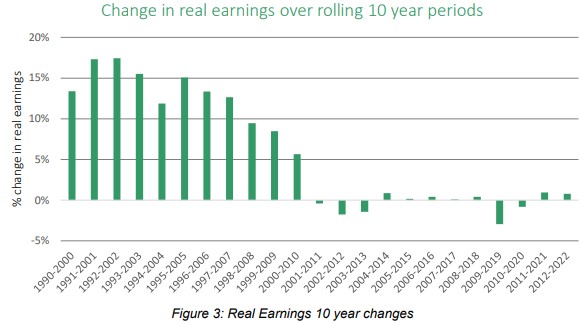

…and, adjusting for inflation, each of us is no better off than we were last year (or the year before).

Figure 3 shows the change in real earnings (real simply means we have adjusted for inflation as inflation means that £100 today buys less than it did last year). It shows that the most recent ten year period which saw real earnings grow by more than 1% was 2000-2010. Since then real earnings have barely grown. Jersey has a productivity challenge.

Does low and falling productivity matter that much?

Yes. Low and falling productivity affects us all. It matters individually as if productivity had continued at 2007 levels we would all be £14,000 a year better off. This is more than £1,000 per month …..for not doing anything extra. Who wouldn’t like to be better off for the same hours worked? It matters collectively too. Higher productivity means higher living standards (and higher pay); it creates opportunities for stronger public services and higher tax revenue without higher tax rates. Higher productivity benefits businesses through lower costs of production and higher profits and creates a vibrant economy and an attractive place to live and work. Higher productivity also enables sustainable and higher rates of economic growth at lower levels of population.

Demographic shifts create another challenge.

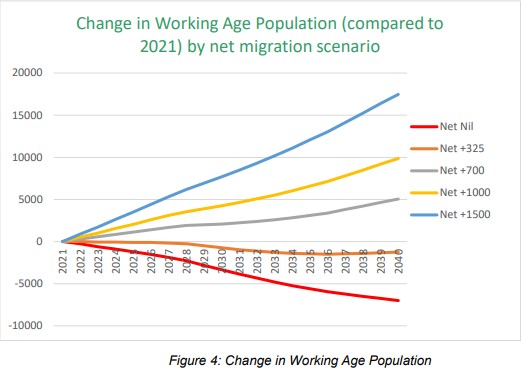

Productivity may be the answer to the challenge that demographic shifts Jersey is facing. Life expectancy is increasing across the world as improved healthcare, medical advances and better quality of lives all enable people to live longer. At the same time, western economies are seeing falling birth rates. These demographic shifts are particularly pronounced in Jersey – 65.9% of the population was of working age at the time of Census 2021 (broadly unchanged from 2011), but by 2040 the share of population of working age will fall to 58.9%. Indeed, the number of people of working age is expected to fall unless there is net migration of around 500 people a year.

And, under all net migration scenarios the ratio of people of working age to people of non-working age falls from 1.93 (Figure 4, below).

Increasing life expectancy is a sign of economic success and is something we should be proud of, but it also creates a responsibility for us all to ensure that our retired population enjoy a good standard of living and are cared for. A falling ratio of working age people to non-working age people makes maintaining living standards (defined as GVA/person) a challenge.

The challenge for Jersey to how to maintain living standards in the face of demographic shifts and low productivity…

In 2040, assuming no net inward migration, Jersey’s population will be roughly the same as now (104,000) but will have fewer people of working age and more people in retirement. Assuming productivity (output per person) doesn’t fall, Jersey’s economy would be smaller in value in real terms (after inflation) than it is today. In turn this means that living standards – GVA/person – will fall. We will all be poorer than we are today. Indicative modelling suggests that in order to maintain living standards (GVA/person) Jersey’s population might need to increase to 150,000 by 2040.

…significant population growth, is, in the words of the Chief Minister “unacceptable”. The Future Economy Programme has been established to look for ways to deliver increased economic growth without population growth.

The challenge for Jersey is to find ways of maintaining the value of the economy without significant population growth. Improving productivity – the value of output produced by each worker – is key to this. The more productivity growth that Jersey can deliver, the less population growth that will be needed simply to maintain living standards.

What can I do to increase productivity?

Collectively we need to find ways of enabling Jersey’s economy to grow without working longer and without relying on population growth. This means enabling new high value industries to locate in Jersey, it might mean upgrading infrastructure to enable each and everyone of us to be productive. It also means existing sectors (including the public sector) need to find ways of working more efficiently whether through adopting new technology or new ways of working, or through upskilling workers or through capital investment, or by serving export markets. It also means exploring the potential of new high value sectors – such as wind farms – and the role they might play in increasing productivity and economic growth. Throughout history, Jersey’s economy has shown it can adapt to change. Collectively we need to harness this ability and help Jersey’s economy evolve to meet the new challenges it faces.

blog.gov.je

blog.gov.je