Commuting by bike is a choice that many of us have long considered to reduce fuel consumption, for the benefit of the environment, and to simultaneously improve our physical and mental well-being. Depending on our individual ages, many of us can remember previous decades when we wouldn’t hesitate to pedal off at the drop of a hat to visit friends, go to school/work/shopping or whatever; even though hardly anybody wore helmets back then, roads and vehicles were all more dangerous than now and we didn’t have many (if any) designated cycle-paths. With many families only possessing one car at the time, and without so much artificial (screen-based) stimulation within the home, there’s no wonder that cycling wasn’t seen as a chore but rather as a treat. Cycling wasn’t viewed negatively for being harder and slower than driving. Rather it was viewed positively for being easier and faster than walking. It was a ticket to activity, freedom, independence and fun.

The modern perception of cycling having become more dangerous is clearly driven by the availability of so many easier options, rather than any actual evidence. Options such as driving to get whatever you need, or simply staying at home and waiting for it to be delivered, or simply plugging into a screen to simulate whatever excitement you are craving. However, if we address our desire to get fitter and to be greener, then we would not only reduce the perception that cycling is dangerous, but we would also reduce the little bit of danger that is actually real. How would this be? Well, imagine if suddenly the number of children who cycled to school and adults who cycled to work was doubled… Firstly, there would be a noticeable reduction in the number of cars on the roads during rush-hour. Secondly, the increased number of cyclists would have significant traffic-calming effect. Finally, these small steps forward would soon multiply into big steps, because the daily demonstration of numerous friends and colleagues cycling safely, whilst benefiting mentally, physically and financially, would be so attractive that the numbers would pretty soon double, and most likely double a few more times after that.

This might all sound slightly more idealistic than realistic, but there is no denying a certain amount of logic and plausibility. Maybe this will be the year that the theory is either proved or disproved, because many people have wanted to switch from their cars to their bikes for a long time, but perhaps the final push is coming now, due to the excruciating hike in fuel prices. So, if now is the time to finally put our good intentions into practice, then let’s look at how we can work with the weather in order to make the experience as easy as possible.

You may have heard people say, ‘there’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing’. Well, rather than debating the aesthetics of hi-vis lycra, at this point, let’s firstly substitute the word ‘clothing’ for ‘equipment’, because that covers so much more than just clothing. Actually, let’s go one step further and substitute the word ‘equipment’ for ‘preparation’, because that covers so much more than just equipment.

Preparation is what weather forecasts are all about. We (Jersey Met) aren’t here to give good news or bad news… one person’s headwind is another person’s tailwind. The comparisons could go on… warm vs oppressive, cold vs refreshing etc. Ideally, what we need to get our heads around, if we want to commit to this new lifestyle, is that every day is a cycling day, it’s just that some days are easier than others. Some days might require 20 minutes for your commute, with no change of clothes. Other days might require 40 minutes for your commute, with a change of clothes in your backpack, and then a further 20 minutes to jump in the shower at work/school, then to dry off and change into those clothes. Some people don’t have showers that they can use at work/school, so for them it will be all about wearing extra layers in the winter and fewer layers in the summer.

Let’s talk about wind

Living on a small island, most of us already pay much more attention to the wind forecast than the average person in Central Britain or France for example. That’s because many Islanders regularly sail, surf or simply want to choose the right beach to sit comfortably on. However, there are still a few people who tend to focus only on the rain aspect of the forecast. Well, if those people are about to start cycling everyday then I can guarantee they will soon start paying a lot more attention to the wind detail.

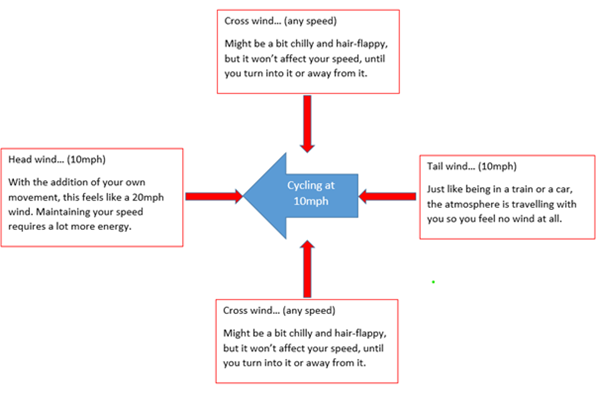

If you consider 10-15mph to be a pretty standard cycling speed then this doesn’t mean that a 10-15mph headwind will keep you at a standstill, because air isn’t nearly as dense as you are (no offence intended). However, if your bike is not electrically assisted then this headwind will make flat terrain feel as though you are cycling uphill. However, if you have a tailwind of the same speed, then because you are so much denser than air you will still have to pedal to get going, but when you are cruising along at your standard speed, then your momentum will keep you going and it will feel about as comfortable as if you aren’t moving at all… your hair will simply hang downwards rather than dancing around and getting in a tangle, your jacket won’t flap around or blow up like a balloon, and best of all your legs won’t have to work any harder than when you go for a gentle walk.

It will take a bit of trial and error to figure out how long your commute takes in a variety of winds, but the usual effect of a tail wind is that it takes much less time and produces much less sweat, so you can usually save yourself some effort by simply wearing your usual work/school clothes. As for the headwind, well you have a couple of options; Option 1 – you can try to stay relaxed, but this will probably double or even triple your journey time; Option 2 – you can try to do it in your usual time, but this will undoubtedly cause such a sweat that a change of clothes will be essential and a shower would certainly be desirable.

Let’s talk about precipitation

We tend to talk about rain or drizzle when we refer to precipitation that comes from massive swathes/blankets of cloud, meaning that it is rather persistent (usually lasting for much longer than the duration of a typical commute). Remember, although drizzle is much lighter than rain you can still get just as wet or perhaps even wetter. This is because drizzle droplets aren’t only smaller than rain drops, they are also far more numerous, leaving very little dry air in between them.

When we talk about showers, then we usually refer to rain that falls from clouds which are quite tall but not very wide (they can produce hail or even snow but if those are not mentioned in the forecast then it’s assumed to be a rain shower). Because showers come from these distinct bubbly clouds, we can usually see them approaching… narrow smudge-like columns extending from the cloud base to the ground. We can often avoid these showers (by diving into some shelter) or we might even outrun them if we can pedal fast enough. However, if you do get caught by a shower, then it could give you a thorough drenching, but it will probably pass you by in a matter of minutes, meaning that you might even have time to cycle yourself dry again by the time you reach your destination.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that you shouldn’t necessarily feel relieved if the rain stops just before you begin your journey. This is because wheels on wet ground tend to throw up lots of spray, which can make you very wet and dirty. You might end up with sodden socks. Your trousers might look as though they’ve been dip-dyed brown. You might even end up with a big brown stripe up your back, looking like a baby who has dramatically exceeded nappy capacity. Mudguards are definitely a wise investment, but in most cases, they are only all capable of reducing the problem, rather than eliminating it. Furthermore, cycle-paths aren’t built in the same way as the roads. Some of them are gritty and sandy. Some of them are made of tarmac, but are smoother and less absorbent than roads, without any camber, making them far more prone to puddles.

Let’s talk about temperature

Like any outdoor sport, high levels of activity can warm you up on a cold winter’s day, even with very little clothing. However, there will be a constant balancing act between that warming effect and the chilling effect of the wind, whether that is the actual wind or the apparent wind (apparent wind is what you feel due to your movement through the air, rather than just the air’s movement over you). When riding an electric bike (as opposed to a push-bike), your activity is relatively low, but the wind-chill is just as high as it would have been. Therefore, the chilling effect would be a much greater player than the warming effect and the need for gloves and thermal layers would be extra-high.

In the summer, by contrast, the main objective is to stay cool rather than to stay warm, and fortunately there are very few days that are too hot to go for a low-effort bike-ride. I certainly wouldn’t recommend trying to pedal up any steep hills in temperatures of 28°C or higher. However, on just such days, a downhill or flat terrain bike-ride can actually be your saviour. This is because, when the air is relatively still, a very thin layer of air becomes trapped next to your skin by all the little hairs and wrinkles etc. This layer of air maintains an intermediate temperature, somewhere between that of your body (roughly 37°C) and that of the surrounding air. However, when you start moving at a little bit of speed, this thin layer of air is constantly stripped away. Therefore, if you imagine a 28°C day, a body that is resting in still air will actually be coated in a thin layer of air that is closer to 37°C, but a body that is moving at speed will simply be coated in 28°C air. Still on the hot side, but much more bearable I’m sure you’ll agree.

Living on an Island, we also need to talk about tides

Being a land-based activity, you might not have thought you needed to consider the tides in relation to cycling. However, spring tides are very common (in Jersey these are high tides of 10.5m or more), they occur over a 3-4 day window, with every new moon and full moon (and we get one or other of them every fortnight). This means that for 3-4 days out of every 14 (that equates to 25% of the days of the year) there is a risk of splashes coming over the sea-walls, onto the cycle-path in St Aubin’s Bay and onto some stretches of the coast road in St Clement and Grouville.

Of course we also need a fairly strong onshore wind and/or large waves to make significant splashes, so that reduces the actual hit rate to no more than 10% of days in a typical year. That could also be expressed as an average of about 2-3 days per month, but in reality winds and waves tend to be more severe in the winter, so we actually find that disruptive tides are heavily skewed towards the colder months. An interesting thing to note is that, due to a curious overlap of the solar and lunar cycles, our very big high tides (spring tides) always occur around breakfast and dinner time, whereas our very small high tides (neap tides) always occur around lunchtime and midnight. Given that commuter rush-hours are also around breakfast and dinner time, it’s easy to see the importance of the tidal forecast for those who travel by bike. Perhaps on some occasions, it’s better to choose a route that isn’t so close to the coast.

To summarise

All these aspects of the weather need to be considered together. There are many ways to get wet… coming up from the ground, coming down from the sky, coming over the sea-wall or coming out of the pores in your skin. Amongst other things, the latter is most dependent on the strength and the direction of the wind. Add in the temperature detail, and you are all set to choose the right bike, the right clothing, the right departure time, the right route and whether or not to pack a towel and deodorant. It won’t always be plain sailing, but good interpretation of good weather forecasts will certainly go a long way to help. With that, I will sign off on this blog and wish you all lots of happy healthy cycling!

Footnote

If you are not already a big follower of the wind forecast, then please remember that when we describe wind direction it is where the wind is coming from, not where it is going to. Therefore, a Westerly wind is blowing from St Aubin towards St Helier and an Easterly wind is blowing from St Helier towards St Aubin; likewise a Northerly wind will be blowing from Gorey to La Rocque and a Southerly wind will be blowing from La Rocque to Gorey. Also, please remember that when we describe wind speed, we use the Beaufort scale. Therefore a force 4, for example, is not 4mph but it is within the range 12-18mph.

| Beaufort force | Miles per hour (mph) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – 2 | 1 – 7 | very light and comfortable for cycling, whatever the direction. |

| 3 – 4 | 8 – 17 | very common and not at all risky, but definitely helpful as a tailwind and definitely a hindrance as a headwind. |

| 5 – 6 | 18 – 30 | also quite common, not damaging but quite risky if you are not especially strong or skilled. With a tailwind of this strength, you will go seriously fast with very little effort. With a headwind of this strength, it will feel like you’re going up a steep hill and you will be tempted to just get off and walk. |

| 7+ | 31+ | quite rare (less so in winter)… as above but more extreme. Such winds are often accompanied by foul weather, so unless you are very fit/skilled/determined then it might be best to seek alternative travel plans. |

blog.gov.je

blog.gov.je