Monthly economy note: Productivity growth at the level of a firm is quite easy to understand. At its simplest it means a firm finding ways to produce more value with the same or less inputs; but exactly how the actions of individual firms build up to deliver productivity growth at the level of the economy is more difficult to imagine. Fortunately, economic theory can help us with this. This month’s economic note explores the economic theory regarding how productivity growth happens at the level of the economy and summarises new data and research on what might be driving the decline in productivity in the UK. The note concludes by musing what this might mean for Jersey.

Jersey is facing the twin economic challenges of demographic change and declining productivity….

As previous notes have explained, Jersey faces the twin challenges of demographic change (an ageing population) and declining productivity.

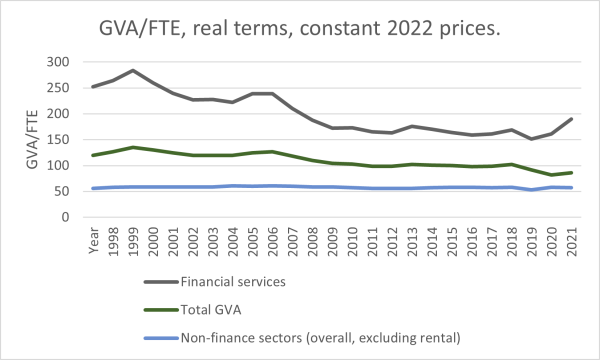

Productivity – defined as output per worker – has been falling since the early 2000s.

Understanding the economic theory on economy-wide productivity growth might help identify what can be done to address and reverse this decline.

….with the latter meaning that over time more workers are needed simply to maintain a level of output.

Productivity – output per worker – is measured by summing up the outputs within an economy and dividing by the number of workers (with an adjustment made for hours worked such that an estimate of the number of “full-time equivalent” workers is used).

So, productivity can be increased by reducing the number of workers and/or increasing the outputs. Either/both can be enabled by investment in capital and investment in skills as both enable workers to produce more from the same or less hours worked.

What does economic theory tell us are the mechanisms by which productivity grows in an economy?

At the level of the economy, labour productivity is measured by the sum of the value of outputs produced divided by the total amount of labour used. The latter is typically measured in terms of hours, or full-time equivalents. Any change in labour productivity is the net effect of changes at firm level, and economic theory suggests three mechanisms by which labour productivity grows in an economy.

1. Growth at the frontier

By developing new high-value sectors and/or by increasing the number and size of “world-beating” or most productive firms, average productivity is increased. There are many examples of this world-wide, but closer to home the development of and growth of Jersey’s financial services sector is a brilliant example of growth at the frontier.

Growth at the frontier raises average productivity by increasing the best productivity.

2. Reducing the tail of under-performing firms

The second mechanism for productivity growth – reducing the tail of under-performing firms – works by increasing the productivity of the least productivity firms. This happens as best practice, knowledge and technology from the highest performing firms spreads through the economy. As this happens, average productivity improves and the spread between the best and worst performing firms narrows.

3. Creative destruction / batting average effect

Creative destruction is a phrase coined by Joseph Schumpeter – an economist of the Austrian School of economics – to describes the process whereby the most efficient/productive firms (and sectors) grow and the less efficient/less productive firms (and sectors) shrink and close. This leads to average productivity increasing and generates economic growth.

In reality, these three mechanisms exist alongside each other and at different points in time (and in different sectors) one mechanism may be weaker and another dominant. Identifying which mechanism is weaker, or which has reduced, can be useful to understand why productivity growth has stalled (and conversely what is driving productivity growth).

Evidence shows that the slowdown in productivity growth in the UK is not due to slower growth by the most productive firms….

It is very tempting to assume that any reduction in productivity growth is because growth at the frontier has slowed. Redressing the decline in productivity growth would, so this argument goes, be easy if only new, high-productive business could be attracted, or via the expansion of existing frontier firms. Proponents argue for tax incentives or subsidies, at firm or sector level or by geographic area, to encourage growth at the frontier. However, UK evidence shows that growth at the frontier hasn’t slowed, but in fact has increased. The UK Office for National Statistics has produced new (experimental) statistics on firm level productivity.

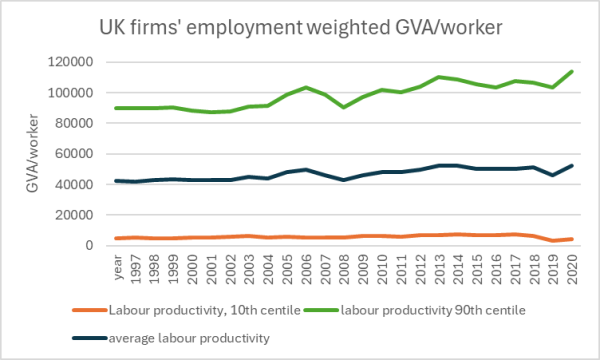

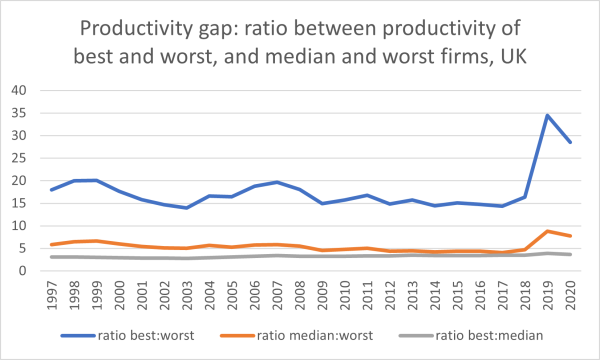

Defining frontier firms as firms with labour productivity that places them in the top 10% of all firms, the ONS work shows that in 1997 workers in frontier firms produced 3 times as much output compared to workers in median firms. In 2021 this ratio has increased to almost 4 times. Figure 2 (below) shows that the productivity of the most productive firms (90th centile) increased over the period 1997-2021.

…..nor is it due to a slowdown in the dispersion of best practice?

The ONS’ work also showed that the difference in labour productivity between firms at the median and at the bottom 10 per cent reduced between 1997 and 2019, suggesting that dispersion of best practice was happening. However, the ratio in labour productivity between the median and bottom 10 per cent increased significantly in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 3 shows the ratio in output/worker between the top 10% and bottom 10% of firms, top 10% and median firms and between the median and bottom 10%. The ratio between best/median and worst firms (in terms of productivity) increased 2019 onwards, but the ratio between best and median was unchanged. This, and figure 2 fit with the theory that growth at the frontier and diffusion of best practice was happening, but also that productivity within the least productive firms worsened.

But a slowdown in “creative destruction” does seem to be playing a part.

Creative destruction can be observed through the rate at which jobs are created and destroyed. Economic theory tells us that the most productive firms should prosper and grow and in doing so will drive out the least productive firms. Workers will move from the least productive firms to the more productive firms, attracted by the higher wages or better conditions that higher productive firms can offer. This creates allocative efficiency and improves economy-wide labour productivity.

Over the period 2001 to 2022, the ONS found that the rate at which jobs are created and destroyed had slowed down by about one-third – ie significantly. Further, this was driven primarily by a slowdown in the rate at which existing businesses grew or shrank. In turn this meant that the reallocation of workers from low to high productivity firms, essential for productivity growth, had slowed. This slowdown in creative destruction is estimated to be responsible for 25% of the decline in UK productivity.

Why has creative destruction slowed?

A number of reasons have been offered to explain why UK firms have become less responsive to changes. Brexit might be part of the explanation via its effects on the labour market – hiring has become more difficult. However, increasingly the evidence points to another factor – unintended consequences of policy decisions. Businesses were supported during Covid (for good economic reasons), but an unintended consequence of this support was that it had the effect of preventing (or slowing down) business failure. In turn this made it harder for the most productive firms to grow as fewer workers were being made available from failing firms – firm level employment growth was 40% less responsive to changes in firm level productivity in the period 2011-2018 than in the period 1999-2005.

And is this relevant to Jersey?

Whilst there is data to back up the conclusion that creative destruction has slowed in the UK and that this partly explains the slowdown in productivity growth, there isn’t the data to back up an argument that this is also affecting Jersey. This, however, misses the point. Creative destruction is both important and necessary for productivity growth. Government intervention can have unintended consequences and whilst businesses might need some support to help them manage a shock or significant change, this support should not be at the expense of creative destruction.

blog.gov.je

blog.gov.je