The start of a new academic year and the start of a period when economic forecasters set out their thoughts (and hopes) of how economies might fare. This month’s note summarises the forecasts made by the IMF and the OECD and considers whether they matter for Jersey, and if so, what conclusions might be drawn.

Before looking at global growth forecasts, it is worth reminding ourselves of the facts and figures for Jersey’s economy.

Statistics Jersey recently released GVA (and other data) for 2022; they have also made changes to the methodology (next month’s we will publish a blog discussing these in more detail) and we now have more detailed data about Jersey’s economy. The headline figures show that Jersey’s economy grew by 5.9% and that productivity increased by 5.0%. This is good news.

However, digging beneath the numbers reveals a more nuanced story. The increase in the value of the economy came solely from the finance, legal and accounting sector, and in turn was due to the effect of interest rates increasing income and profits in the banking sector. The rest of the economy shrank. Similarly, excluding the financial and insurances activities sector, productivity fell by 4%.

Global growth continues to slow……

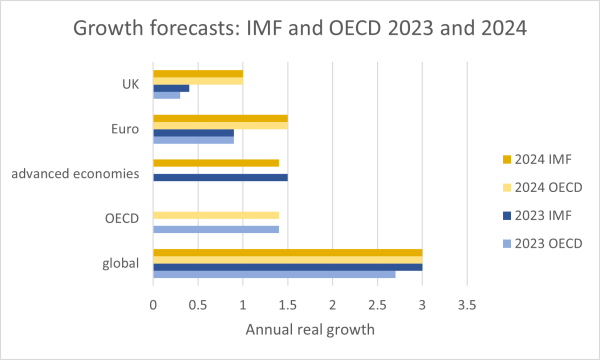

The IMF (International Monetary Fund) and the OECD (Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development) are two of the most highly respected forecasters of global economic growth. Both organisations produce regular forecasts summarising how the global economy will fare in the next and subsequent year, and the economic prospects for regions and specific countries. These forecasts are used extensively and are drawn upon by national Governments and independent economic forecasters alike.

Their latest forecasts point to a slowdown in economic growth that (according to the OECD) will mean global growth (2023) will be at its lowest rate since the 2008 financial crisis, with growth slowing in almost all economies (IMF: 93% of advanced economies will have slower growth in 2023 than 2022).

…..and whilst the direct effects of Covid and the measures taken to manage and mitigate the effects of Covid have largely worked through the economic systems…..

This time last year, the lingering effects of Covid, lockdowns and the disruption to supply chains were still being felt. These direct effects of Covid have largely worked their way through, but have contributed to the inflationary pressures being felt, especially in advanced/developed economies. Similarly, this time last year there was concern and uncertainty about the impact of high energy prices on global economies resulting from the punitive sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. Again, this is largely felt to have worked its way through the economic systems.

…. the indirect effects persist.

Both forecasters note that the pandemic continues to affect global economies in indirect ways. First and foremost, household spending has proven to be more resilient to inflation, and associated higher interest rates, than in the past. At least part of the explanation lies with Covid in that policy responses to Covid (including furlough, working from home, lockdowns) affected households differently. Some households accumulated large savings as their income was preserved (if not increased) whilst expenditure was curtailed (commuting costs reduced to zero because of working from home and lockdowns stopping spend on holidays, meals out, entertainment, travel etc).

These savings were largely unplanned and so households have been content to run them during a period of high and rising prices. In turn this has meant that the increases in interest rates have been less effective (compared to the past) at reducing demand and ultimately prices and inflation – in economics terms this is an example of the law of unintended consequences. It also means that monetary authorities in the US and UK have had to raise interest rates by more (and more quickly).

Covid seems to have affected the composition of demand in other countries too. Spain and Italy have benefited from stronger services and tourism growth (possibly from US and UK households running down their Covid savings); China has seen stronger than expected growth in net exports (again possibly from US and UK households running down their Covid savings). Demand for real estate has changed: this is particularly stark in China where real estate demand and prices have fallen affecting investment decisions too. There are also signs of a shift towards consumption of domestic services – particularly in the US – which has knock-on effects to countries that relied on the exports of such services.

Inflation continues to be a threat

Inflation continues to be a threat to economic growth and the forecasters urge governments to continue to act to control it. In particular, core inflation (stripping out food and energy prices) remains high. High inflation is bad for economies – it is generally accompanied by falling consumer spending which in turn slows down the growth of businesses which in turn affects investment which in turn affects demand. It can also exacerbate inequality as typically poorer households have little/no savings to fall back onto and so during periods of high and rising prices, such households may have to make tough decisions about what to spend their limited money on.

Do these forecasts matter for Jersey?

Whilst the forecasts don’t specifically include Jersey (or indeed lots of other countries) they include forecasts for the UK (which is our main trading partner) and for the Euro area. Further, all economies are intertwined: Jersey’s financial services sector exports most of its services to the UK and other countries; our tourism sector depends on overseas visitors coming to Jersey (and tourism/travel tend to be greater when households are feeling better off which in turn is linked to economic growth); and many roles on Jersey are filled by migrant labour (whose choices of where to work are affected by opportunities available at home and in other countries which in turn are driven by economic growth). Therefore, world economic growth does matter for and have an effect on Jersey’s economy.

What is the outlook for the UK…

The UK’s Office of Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) will set out its forecast for the UK economy in December. This will be a more detailed forecast than either the OECD or IMF provide. The IMF has noted that the UK economy has grown more strongly in 2023 than it, the IMF, forecast. This growth has been driven by stronger consumption growth (possibly the running down by households of Covid savings) and stronger than forecast investment – with falling energy prices and the Windsor framework agreement (which has reduced post-Brexit uncertainty) boosting business and investor confidence. It is worth noting first that the IMF forecasts pre-dates the UK Government’s watering down of net zero rules and renewed uncertainty about the future of the HS2 rail link, both of which are likely to affect business and investor confidence and investment plans. Secondly, the upward revision to UK growth was from a very low base – on the revised forecast the UK economy is forecast to grow by just 0.4% in 2023 and just 1% in 2024 (compared with trend growth of x%).

…and does this mean a recession in the UK is unlikely?

Earlier this month the ONS (the UK equivalent of Statistics Jersey) published its first estimate of how the UK economy grew in July 2023 – the figure was -0.5%. For the three months to July, the figure was +0.2%. The ONS itself says that the monthly figures can be volatile, are subject to revision and should be used with caution, so we should avoid reading too much into a single figure. The quarterly (three month) figure shows that the UK economy is growing – albeit at a slow rate – and not contracting. A recession – meaning two successive quarters of negative growth – seems unlikely; but equally strong growth also seems unlikely.

What does this mean for Jersey’s economy?

All (or virtually all) economies are inter-linked to some degree or another. That said, Jersey’s economy appears to quite resilient to changing global economic fortunes – it was less affected by Covid than many economies (including the UK) and also recovered more quickly.

A continued global slowdown, and continued slower growth of the UK economy, will, nonetheless have an effect on Jersey’s economy. The Fiscal Policy Panel is Jersey’s economic forecasting body and produces forecasts (or assumptions) for key economic variables such as growth in the economy (GVA growth) and inflation (RPI) at least twice a year. Its latest forecast revised down growth in Jersey’s economy for this year (from 3.9% to 1.7%) and revised growth next year upwards (from 1.6% to 2.6%).

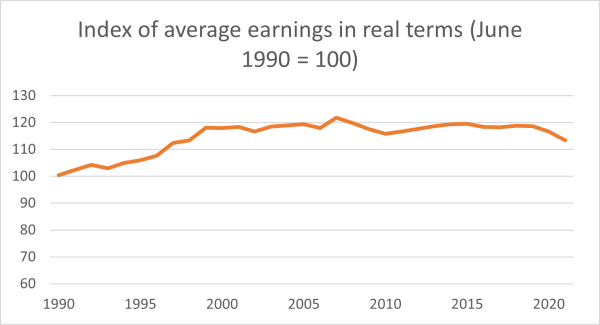

Whether this growth makes us feel happier and wealthier is another question. In recent years, earnings have not grown faster than inflation – real earnings (that is earnings after inflation) have barely grown (as shown by chart 2 below). Average real earnings in 2023 were the same as in 2000.

When real earnings don’t increase, people typically don’t feel that economic growth is benefiting them. But for real earnings to grow we, collectively, need to solve the productivity puzzle that has affected Jersey. We need to find ways to deliver economic growth that are not wholly dependent on growth in the number of workers, or hours worked. Delivering change is never easy, but Jersey has immense potential.

We have control over our economy and collectively can make choices for what we want our economy to look like. Our economy is not immune to the global economy and may get buffeted by economic ups and downs. However, the economy has proven to be resilient (eg strong recovery post-Covid) and it also starts from a strong place (not least because it is largely debt-free). This presents opportunities that other economies don’t have.

The Future Economy Programme has been established to help Jersey find ways to deliver increased economic growth that don’t rely on population growth and later this month will publish its strategy for Sustainable Growth.

blog.gov.je

blog.gov.je